How to reset everything

Diary of a long walk with a good friend.

“I think many of us would consider it quite marvelous if we could set out on foot again, with a clean camp available every ten or so miles and no threat from traffic, to travel across a large landscape. That’s the way to see the world: in our own bodies.” – Gary Snyder

The Unorganised North Algoma District stretches across the hard spine of the Canadian Shield, a vast sweep of rock, trees, and water most Ontarians call “up there.”

We were driving straight up into it from the south. Coming around the bend in Havilland, we saw her for the first time. Mother Superior.

“Inland ocean, man. Big fuckin’ lake.”

Zach, my longtime friend, is an officer of the Canadian Coast Guard at Tobermory. Buddy knows lakes.

The next morning, him and I would hike a tiny stretch of world's largest body of freshwater. It would take us four days.

Day 1

Jimmy greeted us with a hearty two-hander. Put it right there, fellas. He’d drive us to the trailhead.

“So ya picked the hardest hike in the park first. You doin’ the north part too, or?”

“Nope, just straight south.”

“Well ya know you’re not gettin’ a trophy then, eh.”

Known to the Ojibwe as Gichi-gami, or ‘great sea’, Lake Superior is as big as Austria. Very few have trekked its 2,800-kilometre rim. Our route would cover 2.3% of it.

We did not ask that Jimmy elaborate, but he needed no invitation to continue.

“The people before ya, they lost four toenails.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Said they saw a lynx on the trail. Supposed to be a good omen.”

“Hope so.”

Jimmy was the last person we’d see for three days. The German mind cannot comprehend this. Back home, 84 million people are packed into a space three times smaller than Ontario. We began to walk. In the distance, waves hissed on the shore.

A short path led us to a sandy beach. After that came all kinds of terrain: moss carpets, tamarack bogs, boulder fields, rocky ledges, gnarled roots, glacial erratics. Into the lake stretched granite outcrops of exposed Precambrian rock, there since the very first days of our planet.

At one point we emerged from the woods onto an ancient cobble beach 20 stories above the present shoreline—like walking over dinosaur eggs at sea level in the sky. Our ankles held and we were grateful for it.

It was getting close to storm season. In just over a month, cold Arctic air will start colliding with warm air from the Gulf of Mexico. As the lakes, still holding summer heat, feed extra energy into the mix, passing low-pressure systems will unleash ferocious gales, turning the waters savage. They call this the Witch of November.

Fifty years ago, one of the witch's storms sank the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, drowning all 29 on board. Gordon Lightfoot, who grew up not far from where we did, wrote a famous song about it. In the opening, he sings,

Superior, they said, never gives up her dead

When the gales of November come early

—and they say that about Superior because its water gets too cold for bacteria to break down the bodies, which is why they don’t float. Hence she keeps the dead.

I mention this only to underscore a miracle: We had four days of God-given weather. One sun-drenched day after another, air like Swedish midsummer. Nippy at night but never to the bone. It felt like we were getting away with something. All around us the foliage was on fire, a canopy of red, gold, and saffron. Such a glorious Indian Summer was no doubt the work of a higher power—praise be to the lynx!

“Gorgeous, man.”

“Fuckin’ A.”

We repeated this again and again.

After 13 kilometers on the trail, we pitched our tents on the edge of a beach and took a swim. The water was frigid, soothing everything. I drank some out of my hands. Back on shore, arms braced on my hips, I gazed ceremoniously over the cove. Your eyes close automatically when you take a deep breath in a place like that. On the surface I was calm but inside I was bursting with gladness. I walked to our tent and pulled a flask of whiskey from my bag. We each took a sip. Zach combed the shore for driftwood.

“Break off! Break off!”

“What?”

“I’m talkin’ to the wood.”

We lit a pile of pine needles and logs. We poured boiling water into our bags of dinner. The best meal on earth is whatever goes into your mouth after a long hike. The sun went down and the moon got stronger.

“Everything’s coming up Milhouse.”

“It really is.”

Day 2

The morning was brisk. We had oatmeal on the beach and skipped rocks. A moth flew into Zach’s coffee. He’s been eating moths for years so no problem there. No problem getting into gear either; some pain in the hips but otherwise nothing. I thanked my body. Maybe thirty-six is too early for that but I think you should thank your body whether it’s too early or not. We saluted the weather and set off.

It wasn’t long before the language in my head began to change. When I slipped on or tripped over something, I wasn’t upset with it. Wet rocks and fallen logs weren’t in the way. They were only themselves, doing what they do. Being suboptimal for human activity was no fault of the wild. It suddenly became very clear to me that there was nothing to take issue with.

None of this felt extraordinary at the time. In fact, it was barely perceptible. My mind was simply adjusting on its own. Reading Siddhartha recently might’ve made it easier to see things this way, where everything was as it was, ordinary and complete. Or it could have just come from being surrounded by all this wholeness.

Our verbalized thoughts, meanwhile, were far less profound. When Zach and I lived together – first in university housing in Toronto, then in a trap house next to Hooker Harvey’s at Gerrard and Jarvis – we spent hours at night watching YouTube. This was in 2007. When events unfolded on the trail, we’d often quote lines from clips of that era. “Get outta here, you God damn jackass,” from the Winnebago Man talking to a fly; “Fuck it, we’ll do it live!” from Bill O’Reilly freaking out at a teleprompter. I can hear Zach’s wife now, ‘Did you guys just spend the whole time quoting old YouTube videos?’ We did, Katie.

We arrived at our campsite in the early afternoon, in another beautiful cove. I napped in the sun on my sleeping pad and woke up totally lost, then walked into the cold lake to regain a sense of clarity. We milled about and talked nonsense. A jet flew overhead, a bunch of people looking down and thinking, What a nice coastline, Wish I was on that coastline. I scrubbed mud from my shoes with a brittle moss. I didn’t see it, but I knew Zach was eating moths somewhere. We made a fire and prepared the best meal of our lives again.

I had gnocchi, butter, cheddar and bacon bits. Blue-collar umami. We rated our meals. Mine was a nine. Zach’s pour-over braised pork with white wine mushroom sauce was a four, owing to a cooking error. “Pit of the day for sure,” Zach said. We ended each day by reflecting on its peach and its pit. Culinary blunder aside, the day was pure peach from start to finish.

It was a balmy evening. Our gaze swiveled between the sun to our right and the moon to our left. Straight ahead was the unbroken line separating sky and water. We drank Jameson by the fire. After each swig we’d say something dumb or simple.

“What a night, holy shit.

“Unreal.”

“Can’t get over it.”

Day 3

We woke up cold. To our right was some sunshine on the rocks. We made coffee and went there. Nothing needed doing beyond picking the best rock to sit on. That we hardly ever do this says everything about our modern world. Meanwhile, the chorus of Alicia Keys’ If I Ain’t Got You got in my head and stayed there most of the day.

It took the cold shock of a skinny dip to get the earworm out. We sat by the shore and tore into our lunch rations, eating for strength and not out of hunger or gluttony. When I tried to imagine anything better than eating beef jerky naked on a log, nothing came to mind. Wouldn’t have traded it for a Michelin dinner anywhere.

Grace is hard to explain but you can get a good idea of it by watching trout swim upstream. With a bird’s eye view from a bridge we saw their glistening spines on the redds below. Even when they appeared still in the current, they were engaged in constant resistance. This inspired me in ways I can’t quite articulate. As Lispector said of grace, "The discoveries one makes in this state cannot be put into words, cannot be communicated."

That evening, we sat by the fire tossing rocks at bigger rocks. On impact, a rock would burst apart or leave a cloud of dust and we’d get audibly stoked about it. Anyone seeing or hearing us would have taken us for apes. It was pure idiot joy, the day’s peach for sure.

“This is what it’s about.”

“Fucking A, buddy.”

As night fell, we engaged in the oldest, most democratic therapy available to our species: watching embers glow in total silence.

“There’s something about staring into a fire.”

“It just resets everything.”

In a few years, it wouldn't surprise me to see urban wellness studios offer bonfire sessions for burnt-out digital professionals, complete with cacao, gongs, and breathwork. I know I'd go.

Before leaving for the hike, people who cared about me asked what we’d do if we ran into a bear or got lost. I assured them Zach had it covered, though I hesitated to bring it up with him myself. I was already self-conscious about how living in the city had left me untrained for the wild. If I repeated my parents’ and girlfriend’s concerns, I knew he’d hear them as my own.

When I learned he’d packed neither a Garmin nor a gun, and planned to navigate only with a paper map, that was fine by me. In the case of getting lost, his advice to “just go to the coast and then walk down” was plenty reassuring.

I’ve known Zach since first year of high school, when we were 14. In the physical world, which most of us today only occasionally inhabit and where the body may interact with forces, particles, energy, and matter hostile to its well-being, Zach is, above all, capable. (If that sounds like lukewarm praise, look up the definition of ‘capable’). He’s the guy you’d want by your side in a crisis. He can operate all kinds of machines and tie the right knot for any task. He’s a good judge of what matters now and what can wait. I swear he could’ve saved the Fitzgerald. I would trust him with my life.

Day 4

We hiked 13k on the final stretch, for about sixty in total. Zach zoomed off ahead, probably locked in from an edible. My limbs moved without friction and my thoughts were nothing, or several vague things at once. I was just a body. This, I reminded myself, is the goal.

I enjoyed pushing myself to the point of my cells and muscles crying out for stimulants. Snacking on a Clif bar or jerky on the trail felt immediate and vital, serving the same role as coffee but for a far nobler purpose than surviving another day in front of a screen. I could practically feel the protein, carbs and sugars racing through me to where they were needed.

In addition to walking, we also stood, sat, and lay down, often where the posture itself was the whole activity. The Chinese call these fundamental bodily modes the Four Dignities. When I wasn’t focused on one, I was focused on the transitions between them. Each shift attuned me to subtle activations and releases of tension in my body. Such embodied awareness is the foundation for cultivating vital energy (qi). It’s no wonder we felt so alive all the time.

I knew in the moment how fortunate I was, which I usually only realise in hindsight, thinking I should have appreciated things more as they were happening. Out there, though, gratitude came on its own and at all times. I didn’t have to seek it. In fact, it would have been hard work to resist it. In my future nostalgia for this moment in time, there will be no sorrow over its passing—only the joy of knowing I was fully there.

“You seein’ these little blue moths everywhere suddenly?”

“Yeah man, I’ve been eatin’ ‘em.

Back at base camp, things went much the same as in the days before. We planted our chairs by the water, took a dip, and said agreeable things about what we were seeing and doing. Zach announced he was firing up the grill to make smash burgers. Hell yeah, I replied, emboldened by a cold beer in my hand and its attendant masculinity.

Before dinner, I bit into a piece of tropical gum, the chemical tang of which was so electric it actually startled me. For a moment I was surprised by this, then not. Soon we’d back among the fast-casual architecture and McUrbanism of our everyday lives. It was only four days, but it wouldn’t have shocked me to hear they’d started printing people in labs. Last thing we did before bed was look up and see the Northern Lights.

Day 5

Driving out of the woods and onto the Trans-Canada Highway, it was easy to feel like we were exiting the natural world, as if it were somewhere to visit and not the place we inhabit. But the boundary between nature and not-nature is an illusion. While it may seem absurd to put plastic on the same organic plane as a pine, its creation and afterlife are nevertheless part of our ecology. In that sense, we should extend the same care to what we make as we do to what makes us. The same hand that holds a new iPhone each year will cut down a tree without a second thought.

Sitting passenger on an eight-hour drive leaves plenty of room for such thoughts. We passed through town after town of shabby motels, greasy spoons, and little white chapels belonging to one Protestant sect or another. The houses sat on sprawling lots strewn with metal scraps, kiddie pools, hockey nets, riding mowers, firewood, tarps, tires, trampolines, wheelbarrows, discarded doors and windows, and little red slides long abandoned by the kids. One man had plastered the whole front of his house in red letters: CANADA IS NOT FOR SALE!! HELL NO > FU.. TRUMP.

Signs to our left and right announced where to find Jesus and weed and duty-free shopping on the reserves. Only status Indians are meant to be tax-exempt but the shop owners hardly ever ask for ID. We pulled off to get cheap gas and coffee. All the pumps were top-of-the-line and they were building a grand indoor pavilion stocked like a Trader Joe's. How much these Indigenous economic zones benefit their communities depends largely on the competence and integrity of local chiefs and band councils. Still, it was jarring to witness this sparkling service plaza knowing how many First Nations can’t access safe drinking water—a failure on Ottawa alone.

The longer I looked out the window, at the hundreds of lakes, the roads with Indigenous names, the signs with French words on them, at buddy there sittin’ on a steamroller with no mask, inhaling tar fumes and hackin’ darts, the more it felt like home. I had lived in Canada for 18 years, though I was never able to get my citizenship. I’ve now been away for 13. By my next visit, I’ll have had to renounce my permanent residency, and I’ll have no more privileges than a tourist. Nearing home, as the waters of another Great Lake came into view, of Huron’s Georgian Bay, where Zach and I grew up, I just felt really glad to be here.

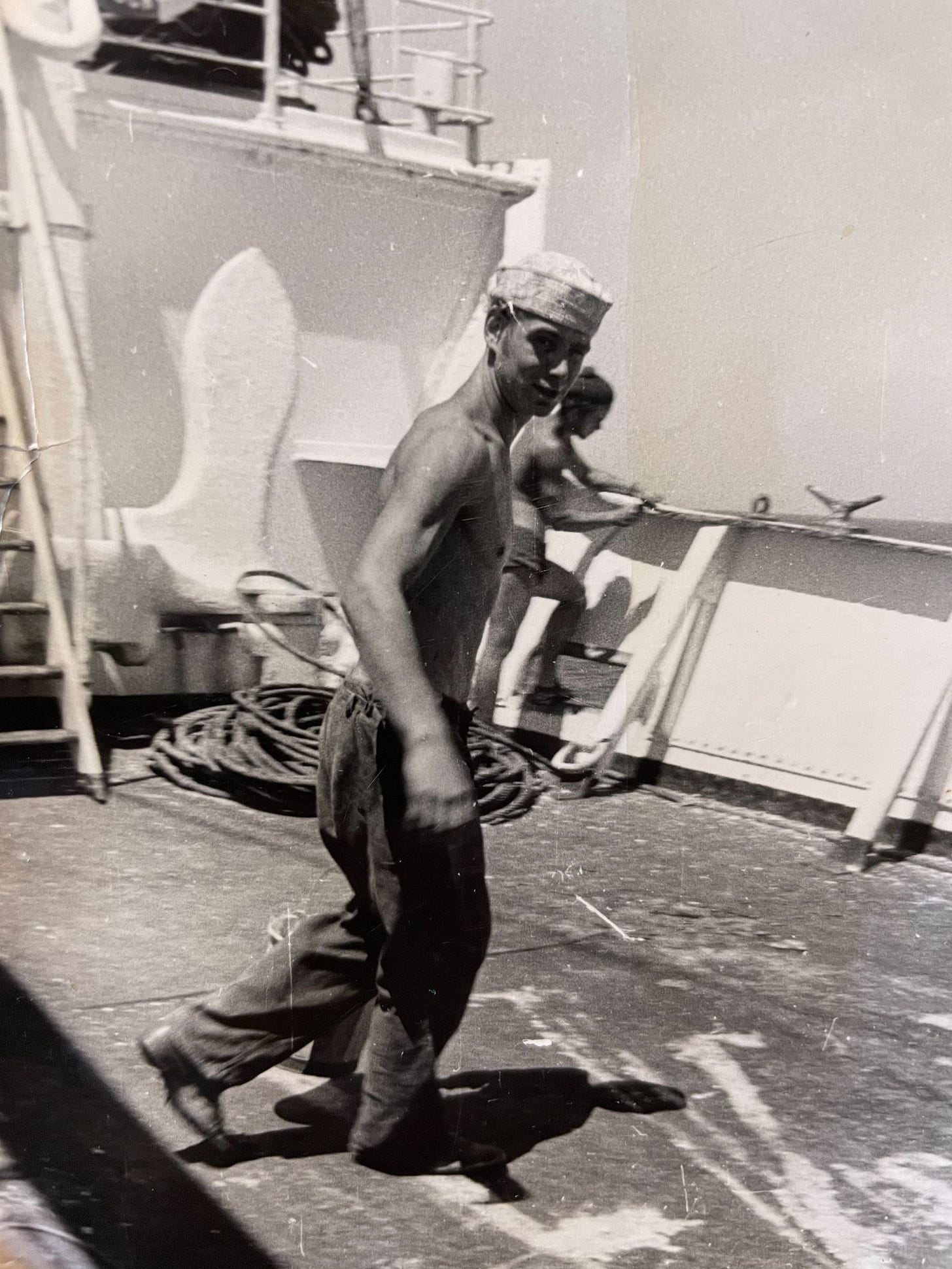

Back at my parents’ place that night, I learned my Opa – my father’s dad – had passed away in the morning. He was 88 and had spent the better part of his life at sea. At 14, with nothing at home, he joined a ship’s crew and was often gone for months at a time. The work was tough but he saw more of the world than anyone in East Germany had the right to expect. He spent the rest of his days telling maritime stories.

In three weeks, we’ll scatter my Opa's ashes in the Baltic Sea. Water, like fire, just resets everything.

Your enthusiasm keeps my writing alive. With every new subscriber to lol/sos, I’m motivated to explore new ideas and share them with you. Subscribe now.

McUrbanism of our everyday lives!

Awesome read, marvellous images. Makes me want to get out into the wild!