Two girls go for a drive and I think about killing a man with a garden tool

A white Cape Town professor named David Lurie makes an ass of himself so thoroughly that his only recourse is to skip town and move way out to his daughter’s farm. One night, three black men rob the place, beat the self-exiled academic near to death, and rape the daughter. So goes Disgrace, the fictional novel by the South African writer J.M. Coetzee. I read it just before we left for South Africa.

People love to tell you how dangerous a country this is. South Africans will say it with sorrow—what a shame things turned out this way. Then there are the tourists, who seem rather boastful about it, as if to say, Look what I survived. The country is mired in the spectre of violence, though the areas it occurs are concentrated and predictable. Violence happens where it always does: where people feel there is no other way forward. It just happens that more people feel this way in South Africa than in almost any other country.

People are killed here in all manner of ways and places. Generally, a distinction is made between urban and rural murder. Inner-city killings make up the vast majority of the roughly 75 daily homicides. For the most part, they’re considered par for the course. Almost all of the victims are black. Disproportionate attention is given to what’s called ‘farm murders’, which claimed 47 lives last year. Since white farmers own nearly 70 percent of the country’s farms, some white activists see the attacks as evidence of a “white genocide” aimed at driving whites out of South Africa.

As the New York Times notes, white beneficiaries of apartheid like to promote the distorted narrative around farm murders in order to solicit international sympathy. And so it was that this self-serving assertion of fact found its way into the simple brain of Donald Trump, who converted it into a race-baiting tweet as he so often does.

In mid-January, Eva and I started a one-month workaway on a farm much like the one described in Disgrace, “at the end of a winding dirt track some miles outside the town.” Like Professor Lurie, we stopped over in Oudtshoorn on the way. The landscape was flat hot dirt. Little else could be farmed here but ostriches. Against the odds, the owners of our farm had managed to sprout an oasis of fruit trees and vegetable beds.

For a week we learned how to tend the property, which, on top of the sprawling garden, included two chicken coops, an olive grove, a natural pool, and a guest house. We were told who to call for power failures and who to call for snake bites. You’d tell the guy which type of snake and he’d either rush over anti-venom or order an airlift. Then the owners left for Morocco, gone for three weeks. On our first night alone on the farm, I got a zoomed-out sense of our place on a map—two dots in the middle of a big, blank space.

The next day, guests arrived. They were two Norwegian girls in their early twenties who spoke a lot without saying much: “The water feels like a warm hug,” etc. I was happy they were happy. Our work was easier without added fuss from faux-spiritual Euro-fairies. Eva made them a basket of fruits and vegetables and we cooked them a nice dinner. They told us all about the healing presence of nature. But it soon became clear that what they were referring to was nature in the abstract, for, after a day of being away from their carefully curated idea of it, the reality became intolerable. The heat, the insects, the gluten—it was all too much. And so they went for a drive.

The following morning felt off from the start. For one, it was the first sky in a week with clouds. But also, the girls hadn’t come home. Their stuff was there but the driveway was empty. Then other odd things happened. The Wi-Fi went out, putting us out of contact with the outside world. An eerie silence fell over the farm and settled into everything around us. Slowly, and then suddenly, the sky filled with the sound of laundering cement. “Is it one of those emergency helicopters?” Eva asked. Its neon orange and yellow gave it the appearance of a floating life jacket. The air thickened as the droning drew closer, heightening our sense of aimless urgency. Eventually, a message came through from a neighbour. “It seems to be theft,” he said of the Wi-Fi. Then I remembered what another neighbour told the owners a few nights before, about cops going around asking about a strange man in the area. From the hushed tone, I don’t think I was supposed to hear this.

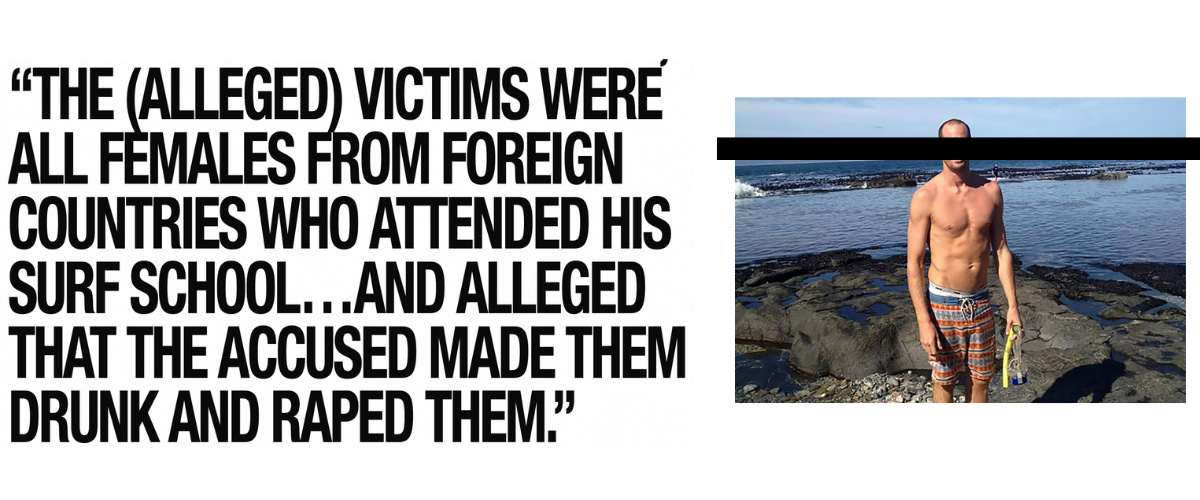

What solace is the police in this country? A few weeks earlier, Eva and I had checked into a surf house in Hermanus. It was the type of place that tried so hard to be chill that it was rather distressing. Even more unsettling was the man running it. He greeted us nervously and shirtless, then strutted around like a cock for some time. I thought he might piss on the leg of a stool in a show of territorial ownership. When he smiled, it was more of a wince, and when he talked, we wished he hadn’t. His every word and gesture sought to affirm his Alpha status. He looked like a left-handed sketch of Vin Diesel.

That evening, Eva and I were sitting on a sofa in the main room of the house. She’d decided to take a deeper look at reviews of the place. There was one from a female guest who said she was sitting by the fire one night when the host and some buddy of his suddenly leaped from a bush, shouting, “The Russians are coming!” and laughing at her horror. Another review advised travellers to look up the guy’s name and see what the newspapers were saying. As Eva was doing her research, I happened to catch him slinking around the ajar front door pretending to hold a shotgun, one hand mimicking a trigger and the other clasping the barrel. Then he pumped it, aimed it at us, and curled the index finger of his trigger hand, followed by an upward jerk of his U-shaped barrel hand. Finally, he tilted his head back and yawned a silent, deranged laugh. Eva hadn’t noticed because she was face-deep in her laptop learning he’d been accused of at least five counts of rape. As for the police, they’d set his bail at $60—the price of one night’s stay at the sex pest surf house.

Standing in the garden, I thought about parallel settings—ours and the one described in Disgrace. I thought about the book’s portrayal of the lawless vacuum of post-Apartheid South Africa, and how little had changed since the year it was written (1999). I thought about how, on our second day alone on the farm, someone had sabotaged our line of communication. I thought of the strange man in the area, and the dangerous one in Hermanus, and the lineage between strange and dangerous. I thought about the $60, and that everything has a price in this country. I thought about how to defend ourselves should it come to that and composed an inventory of lethal weapons: a spade, a steak knife, a compost heap machete. I thought about the helicopter, and about how the Norwegian girls had exactly the type of naïve and glittery disposition misfortune favours. And so it was that, as I stood there swelling with paranoia, all these thoughts coalesced into a horrible, plausible explanation for why the girls were unaccounted for on this eerie, ominous morning.

The outcome of events was that the girls returned in the late afternoon—said they couldn’t sleep on the farm so they stayed at a hotel 40 kilometres away. Why didn’t that occur to me as the most plausible explanation? How did all these details, so disparate in hindsight, conspire to form such a profound impairment of sensibility? More simply: What’s to blame for my worst-case thinking? Am I reading too many gruesome books? Did I spend too much time on LiveLeak in my formative years? Have I taken too seriously my favourite journalism professor’s advice that a part of our responsibility is to get as vivid a picture as possible of the awful things people do to each other? A few coincidental occurrences shouldn’t inspire thoughts of how to kill a man with a garden tool. What I wanted to admit least of all was that I’d been influenced by the residual effect of a Trump tweet.

When you’re in a country where so many conversations end with some variation of “stay safe,” you can’t help but suffer a gradual disquietude. Deep down, I always know everything is going to be fine. Sometimes I just forget.

My brother lives in São Paulo - Brazil, which is not known as a safe city to say the least. One night, he said in the family group chat that he was dining out and I didn't think too much of it. The next day when I reached my phone to text him about something I saw right below his name "last seen on 21:36" and got worried. I called my dad to see if he talked to him, tried the phone tracking app and nothing. My imagination went berserk at this point, in my mind he got robbed and killed and I'm taking a few days off work to fly there and identify his body. This went for a good long hour before he called me and said that his phone was died so he left it charging and forgot to turn it on.

After reading your newsletter I believe you're right. We have to think that everything is fine and we get carried over sometimes by our anxiety. I blame the TV series and the movies.

He looked like a left-handed sketch of Vin Diesel.