*This is a highly visual post. For a better viewing experience, consider opening it on your laptop if you’re currently using a mobile device.

The 1200s were a wild time. In the first quarter of the century, the Mongols had conquered Persia. Next, the invaders, led by the grandson of superstud Ghengis Khan, were coming for Mesopotamia. Meanwhile, the Persian scholar Zakariya al-Qazwini was documenting the entirety of our mystical and material universe in what was Mesopotamia then and Iraq today.

It’s no surprise such an ambitious project should have taken place then and there. It was the Islamic Golden Age, with cities like Baghdad and Mosul at the centre of intellectual exchange. The arrival of the Mongols effectively ended more than 500 years of Islamic prosperity, but not before al-Qazwini had compiled one of the world’s most enchanting works of literature.

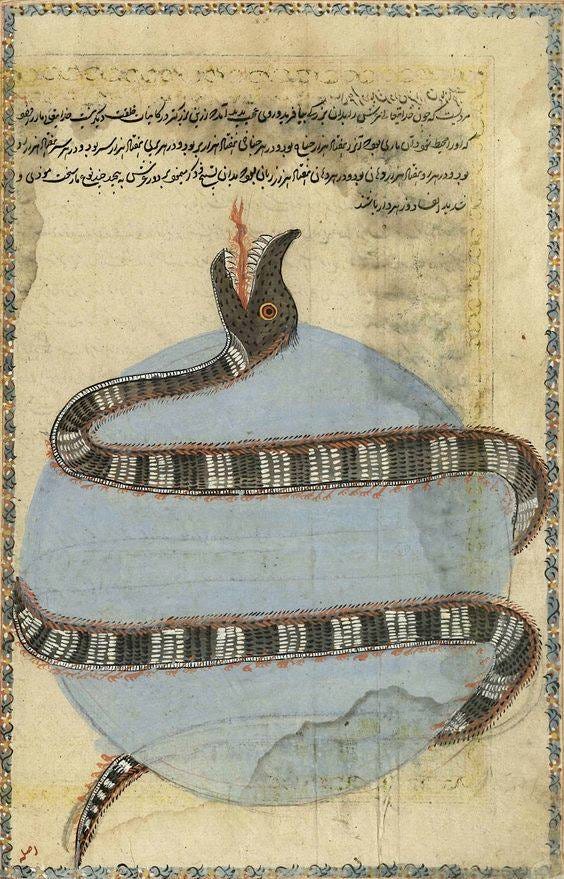

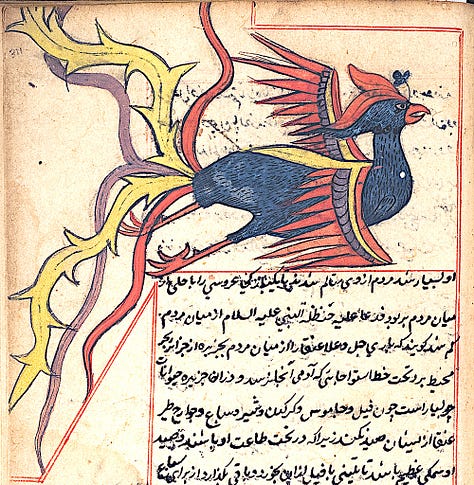

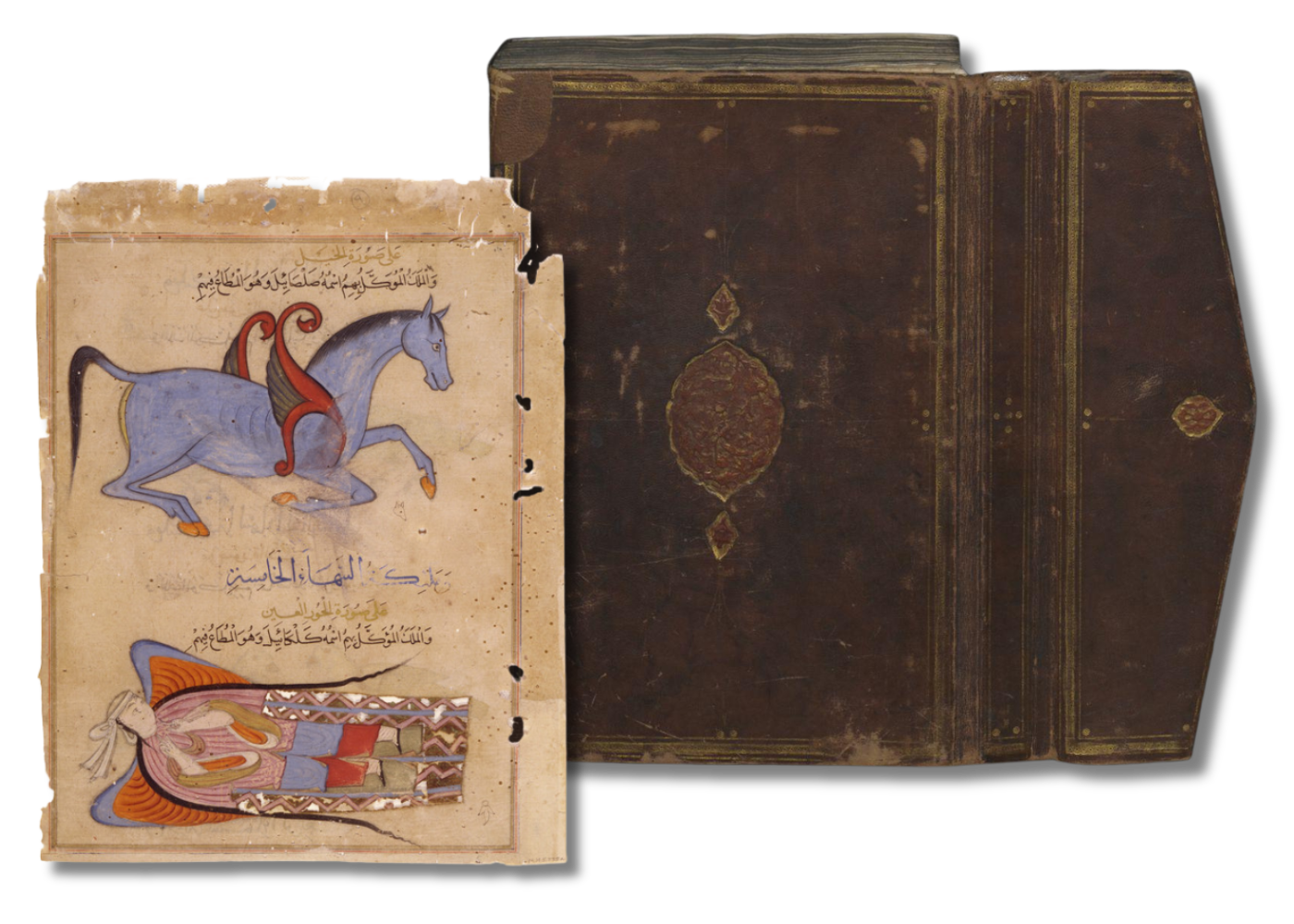

Commonly known as “The Wonders of Creation,” I much prefer the book’s literal translation: “Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing.” In fact, I think it’s a crime to not call it that. It’s a perfect title. The author leaves no doubt as to what readers will find in the 1100 pages to follow. Namely, everything ever. Astral remedies, mythical creatures, the botanical world, human anatomy, geographical lore, and poetry all get their due, among dozens of other subjects. Many of the oddities included continue to defy conventional categorization.

Such is the scope of cosmography, best described as the ongoing effort to put the universe on paper—or, more with the times, the cloud. In Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization, Qazwini would have gathered knowledge from some of the world’s most brilliant libraries, manuscripts, and fellow scholars. Recognizing the crucial role of illustrations in conveying information, he also collaborated with highly skilled artists to lavishly visualize the content of his text.

Your enthusiasm keeps this work alive. With every new subscriber to lol/sos, I'm motivated to explore new ideas and share them with you. Subscribe now.

It was through these visuals, shared on Instagram by the exquisite Public Domain Review, that I was introduced to al-Qazwini’s cosmographical opus. I was completely mesmerized. But also: What is cosmography even? For that, I spoke with M.E Rothwell, whose Substack, Cosmographia, continues the rich tradition of documenting the vastness of all that surrounds us.

A brief chat with

L/S: You hadn’t heard of ‘Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing’. What is your first impression of the work?

M.E.:Thank you for introducing me to it! I’ve done a bit of reading on the work since you first emailed me about it, and I love it already.

The work is divided into two main parts: celestial and terrestrial cosmography. The celestial section covers heavenly spheres, angelology (who can’t love that?), and astrological concepts, whereas the terrestrial part discusses the Earth's elements, climates, seas, rivers, animals (including humans, mythical creatures, and even genies), plants, and minerals.

Al-Qazwini's work is classic cosmography in that it blends factual information with mythical and religious elements. He includes stories about angels bearing the Earth, a giant cosmic fish, and the creation and maintenance of the universe.

It seems to be one of the earliest works of cosmography I’ve yet come across, and will have undoubtedly influenced a lot of the later European scholars, who owe a lot to Islamic scholarship.

What can you tell me about the Arabic/Persian polymath scene during this time?

The end of the 8th Century saw the great Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid ascend to the Caliphate, heralding the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age. In his capital, Baghdad – then the largest city in the world – al-Rashid built the House of Wisdom, a huge public academy and library which soon became the central intellectual hub of the world. Scholars came to study under Abbasid patronage from all across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, and a feverish compilation project began as the Islamic scholars sought to collect and translate texts from all over the known world. We actually have their scholarship to thank for ensuring many works of the ancient Greeks have survived, as their diligent recordkeeping meant they weren’t lost during a period when Europe had little regard for classical science and philosophy.

The Islamic Golden Age, which lasted around 500 years, saw countless polymaths emerge from across the Arabic and Persian-speaking worlds. To name a few: Ibn al-Haytham, probably the most significant physicist between Archimedes and Newton; Ibn al-Nafis, an anatomist and physician who discovered pulmonary circulation; al-Kindi, “The Philosopher of the Arabs,” as he’s known, who fused Aritotelian philosophy with Islamic theology; Ibn Sina (aka Avicenna), a physician and philosopher (who now has a lunar crater named after him); and al-Khwārizmi, one of the all-time great mathematicians.

It would have been in the context of this great intellectual project that al-Qazwini wrote his cosmographic treatise.

What is it about cosmography that fascinates you?

I find its scope utterly dazzling. The word ‘cosmography’ combines the Greek word ‘graphia’ (γεωγραφία, to write) and ‘cosmos’ (κόσμος, universe), and so essentially is the attempt to map the entirety of the universe.

I first came across the term via the great 16th-century cartographer Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594). Cosmographia was supposed to be his magnum opus, chronicling the history and geography of the entire world, and the stars beyond, through maps, chronology, and the rudiments of scientific observation, which was just beginning to get going in Europe. He died before he could finish his project. Perhaps unsurprising—he was trying to map the entire universe, after all!

Why is this important?

It’s important in that it is essentially the entire human intellectual project. We are conscious beings born into a vast, unfathomable universe. Since we developed complex language, we’ve attempted to understand the world around us and communicate a semblance of its meaning to one another. First, we developed animist religions and shamanism, then complex poly- and monotheistic traditions, philosophical enquiry, and, eventually, the scientific method. What is the corpus of philosophy, religion, history, geography, and science if not the attempt to map the universe and our place in it?

What do you hope to achieve with your project?

My goal is to deepen my own understanding of the world and hopefully, by learning in public, that of my readers too. I took the name of Mercator’s work knowing that, like him, the intended goal would always be beyond my reach. The cosmographic project may not even be achieved in the entire epoch of human civilization, let alone the lifetime of a single individual. But the pursuit of knowledge is a noble goal in itself, and to aim towards a target you’ll never quite reach is a way of orienting oneself to a higher ideal. And it's fun!

Do you have a favourite cosmographical work?

As Mercator never finished his, I’d have to go with Peter Heylyn’s Cosmographie. This edges out many other brilliant works (special shoutout to Münster’s Cosmographia, and Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia) partly because it's in English so I, with my philistine language skills, can read it, and also because it includes a whole section called “Terra Incognita.”

There is nothing more exciting than the blank part of a map—the allure of the unknown and the fear, wonder, and mysticism that comes with it. In reading these old works, it’s fascinating to watch these great scholars attempt to grope at a truth just beyond their reach. While the temptation may be to laugh at their mistakes or strange myths, what we’re seeing is the history of humanity’s attempts to understand the world in real-time. It’s a lesson in humility too, of course. Assuming we’ve got nothing wrong ourselves is great hubris; it’s almost certain that in a few centuries from now, our descendants will look back and laugh at the things we take to be true.

Why do you think cosmography lends itself so well to beautiful imagery?

Works like these were hugely expensive to compile and produce. Most arts and intellectual activity from antiquity to the early modern period were done only under the patronage of the powerful and wealthy. Cosmographic works were also a good way of codifying certain religious and political traditions. Kings, emperors, or powerful religious figures commonly commissioned a work of cosmography to legitimise their rule and place them, and their belief system, at the centre of history and the universe. To make a work for a king it had to be, well, fit for a king! Hence many are beautifully decorated with hand-drawn illustrations and maps, made using the best inks, dyes, and parchments. The great Ottoman cartographer Piri Reis decorated his maps for Suleiman the Magnificent with gold.

What keeps surprising you about cosmography?

How many cosmographic works there are out there! So far I’ve only really gotten stuck into the European tradition, neglecting much of the earlier work done by the Islamic scholars. Zakariyya' al-Qazwini’s work is a case in point.

Is cosmography still relevant today?

Absolutely. The current strictures governing academia and its funding have pushed the various fields of knowledge into silos of increasing specialization. In valuing and rewarding depth over breadth, we have created an environment where we have deeper trenches of understanding than ever before, but little, if any, tunnels between them.

In its vast scope, cosmography is the art of mapping the whole. There’s room for more of that.

How might the field continue to evolve?

The modern use of the word ‘cosmography’ relates to mapping the large-scale features of the universe (things like galactic superclusters, the accelerating expansion of the universe, etc.), which is fascinating in its own right. But I’d like to see a revival of the old notion of cosmography too. The idea of seeking to map all fields of human knowledge into a single working whole.

Could it be said that the Internet is our species’ most expansive cosmographical work?

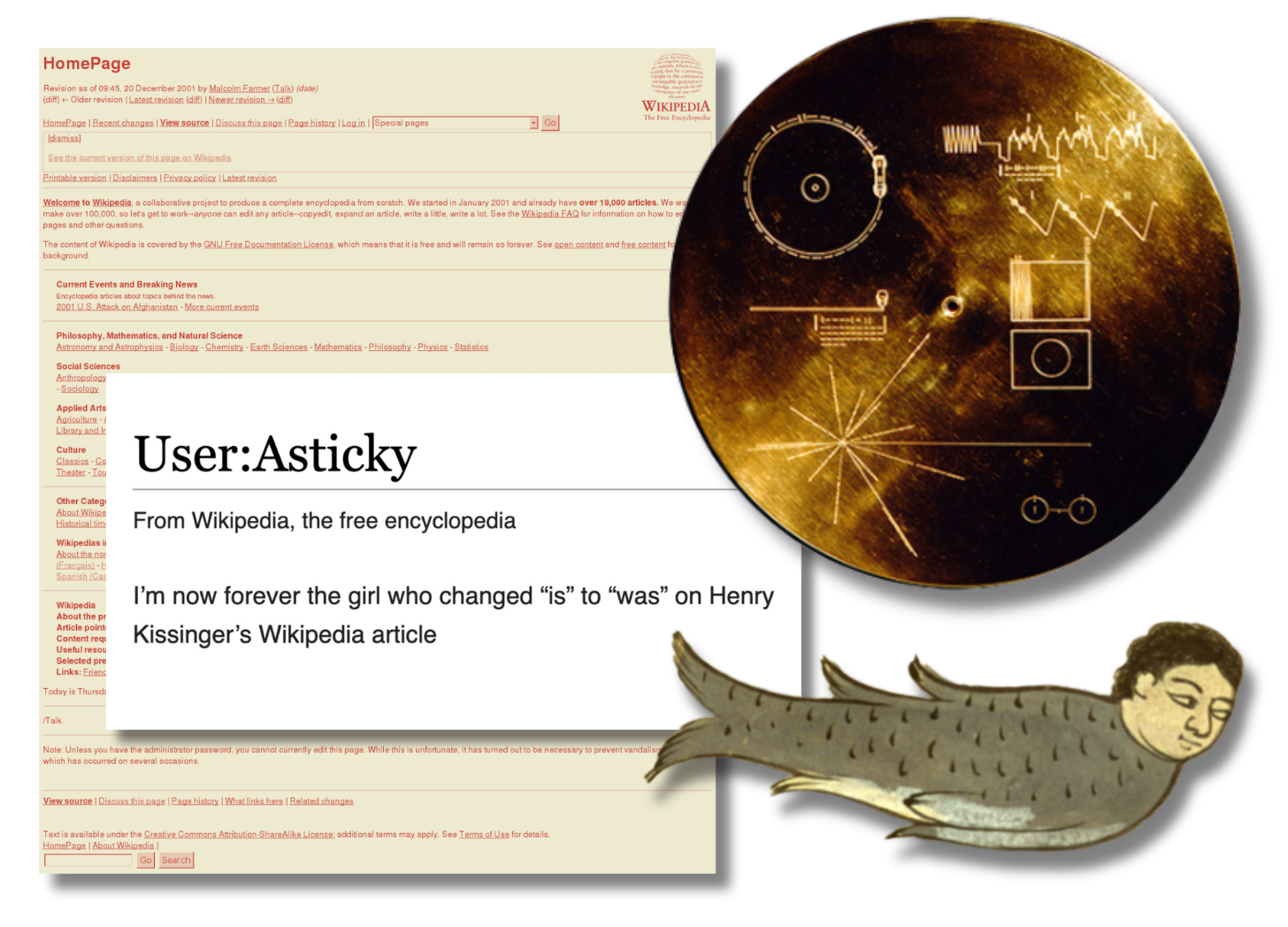

Fascinating premise, and one I’ve not considered before. It’s been said of the internet that it’s the collection of all human knowledge, but in truth there’s much of the old that still has to be digitized and made public, and much of the cutting-edge scholarship is kept behind paywalls in journals and databases. There’s also just a lot of crap on the internet; one would hope that a cosmography would be an attempt to distill as much knowledge as possible. Perhaps more analogous to a work like al-Qazwini’s would be Wikipedia. For all of its flaws, it is amazing that a volunteer-led, non-profit website is the most accessible gateway to a compendium of humanity’s collective knowledge. Its hyperlink system could be likened to a sort of map.

I recently read an excellent essay, “Wikipedia and the Death of the Expert,” from 2011, which challenges the idea of a single authoritative voice and promotes a collaborative approach to knowledge creation and dissemination. Highly recommend.

Say we become extinct. Which cosmographical artefact of our species would you hope aliens find?

A great question. Can I say Wikipedia again? Can you tell I’m a huge fan? If not that, then perhaps the Golden Record, a sort of time capsule that was launched into space aboard the Voyager spacecraft in 1977. Seems to me to be a great attempt at distilling human history and our understanding of the cosmos into a tiny interstellar package. Plus it contains Mozart, so at least the aliens will think us cultured.

As beautiful as it is fascinating! 🙌

This was great!

So thought-provoking and insightful!